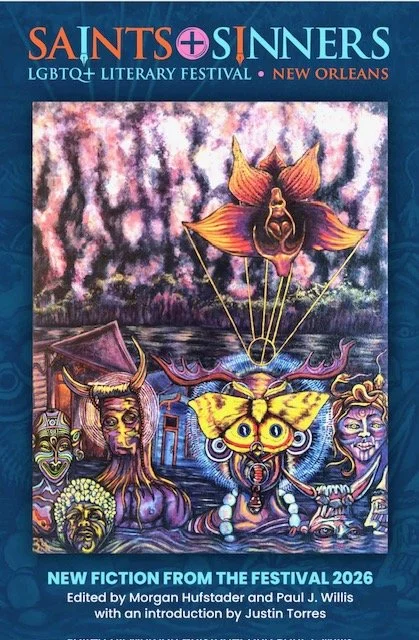

2026 Saints & Sinners Fiction Prize

J E F F W A L T

Runner-up

Really Loved by Jeff Walt / selected by Justin Torres

Nikki had to be taught a lesson, we decided, easily, the way kids decide what to grab from the refrigerator. But then there was the revenge and that required thought—consensus, conspirators—though we didn’t know those words: Rowdy and me, sitting at the kitchen table that bicentennial summer afternoon, a fly strip above us, a fat one still buzzing, legs kicking. Days away from his tenth birthday, we scarfed down cold pizza from St. Charles and bottles of warm Pepsi while hatching our plan: we were tired of being awakened before noon every day by Nikki, the girl who lived right next door in the house where her grandmother, Mrs. Carson, had died; a lumbering dork in the same grade as my brother. Nobody liked—or even loved—Nikki. And her payback for being the neighborhood pain-in-the-ass was coming quick—and, after all, we had it in our blood, in our very cells—to make the worst happen, to keep her away for good. Who cared what happened to that girl?

Not LeAnne, her mother, that was certain. I knew it for a fact. I’d overheard LeAnne talk in disgust about how big Nikki was when she was born—almost eight pounds. How she had to push and push, and drugs weren’t enough; how Nikki stretched and ripped LeAnne slowly until she felt herself snap like a piece of fair taffy. She blamed Nikki for the strands of grey in her red hair; for stretch marks; for stealing her youth. Heather, Nikki’s little sister, had been a preemie. LeAnne said having Heather was barely a burp, then laughed, sipped her beer. Heather had LeAnne’s naturally curly hair and petite features. LeAnne spent summer evenings sitting on the top step of their front porch with Heather on the step below her, between her legs, brushing Heather’s blonde locks that bounced back from the brush—a tiny Miss America; hair that LeAnne rinsed with beer; blonde hair that she conditioned with whole milk; full hair pulled up in a fluffy ponytail or long, squiggly piggytails, or swirled upon her shoulders like a child Farrah Fawcett. Heather was really loved, completely loved, and surely spent many nights sighing in lavish sleep between her mother and father while Nikki slept alone in her attic room without even a doll. Heather had not yet learned to cross the ditch into our yard. But Nikki could jump it backwards. And now she had to be stopped.

I was their babysitter and watched Nikki and Heather almost every night during the summer while her parents got drunk down at the VFW. I knew about Nikki’s life, so I was the perfect co-conspirator; I knew she ate Fruity Pebbles every morning, that the family’s shag smelled like Carpet Fresh and if you laid on it you’d have to wipe some of the dandruff-like crap off your shirt when you got up; I knew she had a diary that I never wanted to read; that she wanted a horse; that her father cut her hair by literally putting a bowl on her head—and the bowl was becoming too small. I knew, too, that her mother had a stinky vibrator in her underwear drawer, and that her father used Right Guard.

I loved those summer nights when they came home late after a sweaty, red-eyed night out, reeking of tobacco. Most nights JD had to put LeAnne to bed before paying me. Five-year-old Heather was always out solid, eyelids fluttering a thumb-sucking dream as she lay on the recliner. The TV playing Twilight Zone reruns. Nikki was in her room and knew better than to come out at that hour. I never knew when they would be home, but usually after the bars closed. Waiting for them was like waiting for morning on Christmas Eve. LeAnne tumbled through the front door, sometimes with her bra in her hand, her Lee jeans unbuttoned, her beer gut swollen. JD would guide her to their bedroom, undress her, ask about the kids. I’d stand in the doorway of the bedroom, shrugging my shoulders coyly, maybe sucking on a lollypop or licorice, one leg propped on the other with my foot, saying nothing.

I watched LeAnne’s pants come off often—her panties always slid down a little. The matted red hair mashed beneath made me think of what my uncle Jack always said, that a woman’s carpet should match the drapes. LeAnn was red all over. JD left her in her top, usually a tight T-shirt—her stained favorite won playing the ring toss at the Clearview County Fair that read, “Pennsylvania Girls Do it Best”; her red hair wrapping her blush-mascara smeared face. I waited for the night when JD would be drunk enough to undress too, the night he’d be so tired he’d ask me to stay the night, to be there in the morning for the kids. Most nights he just paid me and I left. That night that was more like a Christmas morning. He sat on the couch and pushed his hand through his vinyl-black hair, said, “Shit, that woman’s gonna kill me.” I said nothing, just went to the fridge and brought him a cold Bud.

It was a hot night—even the crickets weren’t singing. LeAnne snored like a trucker. JD had taken off his boots and torn socks. His dirty feet smelled like vinegar. Lit by only the TV, JD was a hairy mix of Burt Reynolds and Tom Jones, and the dad from “Land of the Lost.” I wanted him to want me to rub his feet. I knew I could make him feel like he wasn’t gonna die, ever. He put the sweaty beer to his sweaty, rippled forehead, laid back and closed his sad eyes. “Yeah, one of these days, I’m just gonna wear the fuck out.” I told him to take his shirt off—reminded him folks had died just that day of heat stroke. He moaned a, “Yeah,” then pulled the white T over his head. The shirt lay crumpled and sweated and I wanted it badly.

Finally, I could see his hairy chest up close—hairier than any of my uncles. Dark fur with flecks of grey swirled up and then back down to the center of his chest with a thick line straight down his torso to the belly-button. I wanted to be his kid. I wanted to be Nicole or Heather and have the luxury of laying upon that chest whenever I pleased; him wanting it, too, because he would love me—really love me, like Heather, maybe even more. I wanted it at that moment. Wanted it when I watched him mow the lawn; when he planted the garden; when he was greasy and bent over the engine of their Ford. I wanted it even in winter when hidden beneath a flannel shirt or oil stained Carhart jacket. That night, I prayed he’d be completely drunk and high and hopeless, and that he would take his pants off, too. I already knew he wore Fruit-of-the-Loom underwear, stained in the front and back, probably a bit too tight, I imagined, since he was just about six feet tall and thick. He just sat there like an oaf—like Nikki—in his tight Levis shaking his head about whatever trivial stupidity happened with LeAnne that night at the VFW. Something that didn’t matter to me.

He mumbled that he saw my mother with Skunk McFarland—as if a falling star had crossed the sky, as if his wife had grown a third tit, or Harley, his cat, had just shit a golden egg. Nothing Kitty did surprised anyone. He saw, too, my Uncle Peek-a-boo picking a fight with Donna and The Heartbreakers, his old band. Gigs, Whitey, Butch, Fat Tits, Jack, Aunt Nan—they were all there, of course. That’s how they stayed cool summer nights and warm in the dark winter. Bands played almost every night at the VFW or Windmill Tavern or Coke’s Place.

JD and LeAnne were no different than my uncles and the rest—except JD never seemed to be “laid-off” from Harbison-Walker. If he could sing, I was sure he could have been big as Johnny Cash or Conway Twitty, but I knew, too, his only talent was sex. I heard LeAnne telling my cousin Tubbs once how it felt like Heaven and the angels and the Devil inside her all at the same time when they did it. I wanted some of that good feeling—warm inside the way she described it to Tubbs. Since I didn’t have a father, I never knew what it was like to cuddle up to a man. None of my uncles did that kind of stuff, and when I tried to smell them, or trick one into holding me by pretending to want to wrestle, they’d just push me away.

So, there I sat with JD, certain that summer night could be my best Christmas Day, but he just rustled my hair and told me I would make a great father one day. Heather began to squirm in the poofy, cat-scratched recliner, which had become her crib. He stood, yawned and said, “Time for me to hit the sack, kid.” After 2 AM, he headed toward the bedroom, whispered, “Thanks,” and winked. The bedroom door was still open after he went inside, so I paused and watched his vague body as he fell back on the wincing bed; LeAnne farted and he sighed deep as if he had lost all his money in a poker game, and then turned his back from her toward the bright face of the clock. I stood on the porch looking up at the stars for the Big Dipper—the only one I could identify. “Fuck,” I said, and jumped the ditch that separated our yards.

***

JD and LeAnne, me, Rowdy, and my mother would sleep till way past noon as we did almost every summer day. Nikki and Heather would get up early, play in the yard, pull cherry tomatoes from vines, fight, or swing on their rusting swing set. Mostly, however, Nikki jumped the ditch and kicked around Wiffle balls or thumped Rowdy’s basketball on the loose boards of our porch. My mother deep in dead-sleep, Rowdy and I would yell from our bunk beds, “Go home, you stupid bitch!” She didn’t hear us, we knew, and we were too lazy to get up and kick her ass.

Rowdy spent his nights with Chink and Elmo, or Darrell Ladow, or the Lope brothers—teen punks, losers, dopers, dog-killers; my brother their mascot, their car radio-stealing apprentice. Guys just like my uncles, and their uncles before them: foul-mouthed and dirty-nailed. Men who laid bricks, mined, drove trucks, or fried chicken at KFC.

Sitting at the kitchen table dipping our slices of cold pizza into a jar of Ragu: Nikki had to be taught a lesson, one that would keep her on her side of the ditch, at her house, waking her parents after a night of dancing, and not biting into our summer break. This scheming brought me and Rowdy together. Normally, we plotted and practiced ways to eliminate one another from life on Good Street; ways to have Billy Martell, our sick, limping collie, to ourselves; to have the bedroom; the couch; the TV; the skateboard. But this day, we were solid, a one-brained animal plotting to snuff out the enemy who cut short the solace of our nightly dreams: Nikki, the dog-faced stutter queen with a bowl hair-cut and boyish features and gangly ape-walk, hair above her lip. And, of course, she had what I wanted—her father—even though he didn’t do much than yell at her, she at least breathed his air, knew his smell, his pillow, his sweaty work shirts. Surely, at some point, I was certain, JD must lie in front of the TV bare-chested, that she could easily slide in beside him, rest her head on his stomach or nestle in the arch of the charming odor of his armpit.

Rowdy suggested we hog-tie her the way our cousins did their pigs, but I said, “Then what?” Tying someone up wasn’t enough. Whatever we did had to stop her—keep her away for good. He suggested feeding her Billy’s dog shit. A possibility. Maybe, I said, we could piss in a Mountain Dew bottle and offer her a swig. No, that wouldn’t work. We had brainstorms: feed her a bottle of hot peppers until they came burning up from her stomach; push her into the sewer ditch; lock her in our basement where rats scurried around the furnace. Finally, Rowdy, of course, had the best idea of all. In fact, the light bulb was so bright and head-on and sure-fired that we decided to go for it on his birthday morning as a present when Nikki was certain to turn our rickety front porch into a soccer field or a one-man circus complete with stomping elephants. Rowdy would be ten that day, and the old, second-hand tent would be up in the yard for the Fourth.

Rowdy and I had different fathers. When our mother, Kitty, got ugly drunk, she’d tell Rowdy he was a one-night stand, and who knew where his son-of-bitch father was. Kitty meandered between AA meetings and six-month binges, seizures, shakes, Librium, Valium, Seagram’s & 7, more AA, etc. At Thanksgiving and Christmas, we stood in the Goodwill line with her for the box filled with donated instant stuffing, instant coffee, a can of turkey gravy, a can mold of cranberry crap we didn’t even eat, and a gift certificate for a free turkey at the A&P. She scooped up boxes of government cheese and generic groceries. She sold our Food Stamps buy cases of beer.

Men loved Kitty, even proposed, but she wasn’t the kind to settle. They gave us kids money to disappear: quarters out of the house, get lost, to go buy a soda at the Aquarius Pet Shop several streets away. I always took the money quickly, but never vanished: I would sneak back into our house through the back door. The men, of course, quickly seduced our drunk mother. That’s how I saw my first penis—and the second and third and so on. Once she screwed our landlord to pay the rent. Once, my uncle Vic walked in the front door while one of the men had my mother’s pants off moving his fingers up inside her while she was passed out on the living room couch. I was silent, hidden. Vic screamed, “You dirty son-of-a-bitch, git the fuck out of here.” The man ran with the smell of my mother on his fingers, with the fear of a burglar getting caught. Kitty, however, didn’t flinch, couldn’t flinch. Vic moved her head back and forth while she lay there numb, half-naked, spread eagle. He sat beside her where the man had been. He touched her thigh with the back of his hand and slowly began to work his hand just like the man had, but only for a minute before pulling an old throw from the back of the couch to cover her. I squeezed the quarters and then quietly snuck out the back door and ran four blocks barefoot to buy candy.

Rowdy pondered what he’d get for his birthday, which was usually forgotten, so I didn’t imagine anything like a bike or Atari to appear. The July Fourth party, he always thought, was a big celebration for him, but was actually a beer bash for the neighborhood. More for Kitty than Rowdy. Fireworks bloomed in sky way into the night. Snakes, Missiles, Smoke Cones and Cherry Bombs. I wrote “Happy Birthday” in the night with a sparkler without showing it to my brother. I drank a couple beers. Someone gave Rowdy a joint and he didn’t even choke hitting it. Nikki ran in circles, fell, got up, fell again like an oaf. LeAnne brushed Heather’s hair as the cherub sucked her thumb and pointed to all the colors showering above her. JD smoked Marlboros and cracked can after can. I’d stand close to him, but he didn’t say a word. Often he would sneak behind the old camping tent to pee and I would follow, trying to see him. He swayed as he pissed, then shook it, but I never saw anything. So, I whirled and twirled into the smoky night. I tried to trip Nikki or push my brother into the hard ground; played with the feathered roach-clip in my hair. The night choked my throat, a swampy miasma that slowly floated and swirled as if we were in hell. This was my mother’s perfect heaven: a circle of lawn chairs, coolers full of floating beers, blur on blur, a front yard bonfire, nothing beyond the light but more temporary happiness filling the sky. No cake for Rowdy, just Roman Candles and a kid who felt, perhaps—a least for a day—the brightness was all for him.

The next morning, everyone slept: Tilt on the couch, Big Carol of the floor, Skunk and Mac passed out in my mother’s bed. Nikki awake, of course, kicking Rowdy’s football on the front porch. My brother, bleary-eyed, crawled from his top bunk, slapped me, and said, “It’s time.” Sill in our clothes from the night before, we reeked of firecracker smoke and booze and weed. Outside, Rowdy went directly—as planned—to the dilapidated tent, one corner coming loose from its spike. Nikki had moved on to hopscotch. Tiredly, I invited her to come smoke a cigarette in the tent with us to celebrate Rowdy’s birthday. She smiled stupidly then slipped through the tent flap, which I laughingly zipped shut behind her locking her inside where Rowdy waited; I ran to the back of the tent and pressed my face to the nylon screen window and watched as Rowdy wrestled her into a Full Nelson. She wriggled like the fish we lifted with rods from the Susquehanna. I watched him twist her toward him, pin her arms with his knees as she flailed and thrust. No one else was awake and Nikki couldn’t scream for help as Rowdy managed to get his pants down, brushing her tight-lipped contorted face with his nut sack, trying to force his hairless cock into her mouth. The harder she fought, the more he tried. Her lips tight, eyes squeezed shut like a baby being fed something she didn’t want. I could see her dad’s goofy handsomeness in Nikki’s twisted face, his strength in her wild bucking, which finally thrust my brother off. Nikki wailed, once, as if some wild, pre-historic bird flew from the past and out her mouth, then she ripped right through the weak zipper of the tent, leaving a hole that we would never repair.

Our summer mornings for the rest of that year were exceptionally quiet.

We could sleep ‘til noon if we wanted. Rowdy was ten now and almost tall as me. That week, I saw JD naked in my first wet dream. Little Heather caught lice and JD with a cigarette in his mouth shaved her bald on their front porch, her tiny curls cart-wheeling away on the breeze. LeAnne crept, drunk, across the lawn, collecting the blonde curls as she wept and wailed like someone important had died.

Rowdy got his second birthday present from uncle Gigs, a used Buck knife, which glowed and reflected as he stabbed at afternoon air, cutting into dusk, slashing the sunlight’s jugular—back and forth—happily—slash, slash, slash.